Ph.D.

Research Portfolio - Draft

A Participatory Protocol for Ecologically Informed Design Within River Catchments

Name: Joanne Tippett

Course:

Management Research Process - I/GT6351

Tutor:

Dr. Jackson

Date: April 27, 2001

PhD Supervisors: John Handley, Joe Ravetz

Jeff Hinchcliffe (Mersey Basin Campaign)

Submitted as course work for Masters in Economic and Social Research

University of Manchester

School of Planning and Landscape

Submitted

as course work for Masters in Economic and Social Research___________________ 1

Abstract______________________________________________________________________ 3

Introduction___________________________________________________________________ 4

Aim

and questions_____________________________________________________________ 5

Objectives___________________________________________________________________ 5

Wider

Impact of Research_______________________________________________________ 6

Methodology__________________________________________________________________ 6

Research

Questions, Methods and Sampling Strategy___________________________________ 8

Phase

One: The Mersey Basin Campaign - A mechanism for sustainable planning?__________ 10

Phase

Two: The River Valley Initiatives - A mechanism for linking strategic

objectives and local actions? 14

Phase

Three: Testing the DesignWays

Process in a River Valley Initiative_____________ 15

Criteria

for assessment of research________________________________________________ 16

Sources

of data to answer research questions________________________________________ 18

Analysis

techniques___________________________________________________________ 19

Participant

perceptions_______________________________________________________ 19

Metaphorical

modelling______________________________________________________ 20

Reflexivity________________________________________________________________ 21

Ethical

considerations__________________________________________________________ 21

Research

Validity_____________________________________________________________ 22

Contextual

information_________________________________________________________ 22

Alternative

explanations________________________________________________________ 23

Potential

Problems with Research________________________________________________ 24

Weaknesses

in research design__________________________________________________ 25

Unanswered

questions_________________________________________________________ 26

PhD

Timetable - Draft_________________________________________________________ 26

References__________________________________________________________________ 28

Appendix

A: Research Questions for Action Based Phase of Research_________________ 32

Abstract

The overall aim of this research is to develop a design process that encourages participation in integrated river catchment planning and design based on ecologically informed principles, with a view to developing a tool kit for sustainable development at the landscape scale.

This poses three interrelated research questions:

1. Are there generic principles to guide successful integrated catchment planning?

2. What is an effective process of engaging participation in ecologically informed planning and design at the landscape scale?

3. How do these principles and processes fit into a broader theoretical framework?

The overall methodological framework is based in systems thinking, integrating both social science and ecological data. An epistemological framework based on embodied realism provides a dialectic bridge between an interpretive, grounded approach and a framework of commonly agreed principles of sustainability. In response to recent writing on the importance of considering different levels of scale in research into complex systems, the methodology seeks to create a dynamic dialectic between a large scale overview and detailed contextual information to provide depth and a grounded interpretation of actor’s perceptions.

There are three phases. The first two phases involve case studies of the Mersey Basin Campaign both from an overall perspective and at the level of the River Valley Initiatives (RVI), the mechanism for delivering strategic principles at the local and sub-regional scale within the Campaign. They set the context and provide essential information for interpretation in the third, major phase of the research. In this phase of action based research, the researcher will facilitate a participatory planning and design process in a RVI.

This methodological focus was chosen in response to the nature of the research problems and epistemological issues raised in the literature on sustainable development about the need for interdisciplinary, multi-scaled, systems approaches. The emphasis of the research question is on the process of design and communication. This requires a particular focus on participants' perceptions and reactions to the design process. As much of the research into sustainable development is responding to a relatively new imperative and new approaches, it is by its nature often action research, or research in which there is intervention in a system through the agency of the research project.

Introduction

The challenge of sustainable development, the interplay of environmental quality, economic vitality and social equity, lies in learning how to meet present human needs and improve quality of life without diminishing the Earth's capacity to provide for the needs of future generations. Engendering cross-sectoral partnerships and engaging community and business participation in planning is seen as playing a key role in sustainable development, exemplified by the emphasis on public participation in Local Agenda 21 and the cross-sectoral role of regional planning as exemplified by strategies such as Action for Sustainability (Kidd and Shaw 2000; Luz 2000; NWRA and GONW 2000). Researchers and practitioners are beginning to discuss the key role of design in creating a sustainable future (Lyle 1994; Van der Ryn and Cowan 1995; Lewis 1996; Hawken, Lovins et al. 1999). In the field of sustainable planning and management, attention has been paid to increasing public participation in 'integrated assessment' and 'scenario building' (Darier, Marchi et al. 1999) but there has been little attention paid to developing a practical protocol for applying principles of sustainability with a communicable and clear process of design. This research project seeks to remedy this deficiency within the context of integrated planning and design within a river catchment. The research partner is the Mersey Basin Campaign (MBC), winner of the inaugural international RiverPrize in 1999.

The research is characterised by the following assumptions: sustainability[1] offers a valid and important conceptual framework for planning and design, public participation in this process is advantageous and an interdisciplinary approach is essential to understand the complex issues involved in sustainable planning.

Aim and questions

The overall aim of this research is to develop a design process that encourages participation in integrated catchment planning and design based on ecologically informed principles, with a view to developing a tool kit for sustainable development at the landscape scale.

This poses three interrelated research questions:

1. Are there generic principles to guide successful integrated catchment planning?

2. What is an effective process of engaging participation in ecologically informed planning and design at the landscape scale?

3. How do these principles and processes fit into a broader theoretical framework?

DesignWays is a communication and educational tool, developed by the author to apply ecological design principles at multiple levels of scale. During two years of pilot trials in Southern Africa, it evolved into a participatory methodology for applying principles of sustainability. The process embodies three principles: use of patterns and systems theory as the theoretical framework for design, a transparent and innovative design process and engaging effective participation through envisioning and planning for the future.

Objectives

1. Develop transferable principles for ecologically informed catchment management from in depth study into Mersey Basin Campaign and comparative study of successful projects.

2. Develop process of ecologically informed participatory design, the basis of a tool kit for sustainable development.

3. Provide recommendations to institutional players for increasing effectiveness of participation and partnership models in ecologically sustainable planning, with particular emphasis on learning from the successful model of the Mersey Basin Campaign.

4.

Contribute to the emerging theoretical underpinnings of

sustainable planning methodologies.

Wider Impact of Research

This

research is likely to have an impact on both the developing academic field of

sustainable planning, contributing to the theoretical framework of the

discipline, and in the practitioner field. Results will be of use not only to

the MBC, but also to the increasing number of partnership organisations and

similar bodies that are learning from the Campaign, particularly after it won

the International RiverPrize. This research will inform the debate on the role

of landscape and natural resource planning in sustainable catchment management

and the role of public participation in planning at a landscape scale. Models

of best practice and transferable principles for successful catchment

management will be developed and disseminated to practitioners and academics.

The MBC envisages that following the research, the ‘DesignWays ’ process may be developed into a transferable toolkit for

international dissemination through a possible partnership between MBC, the

researcher, Manchester University, the City of Brisbane and the private sector.

This research is important in the context of the European Water Directive (European Union, Luxembourg, 23 October 2000),

which requires member states to create integrated watershed management plans

with community involvement, and in the context of increasing emphasis on

partnership models and public participation in local and regional development

and governance.

Methodology

The overall methodological framework is based on systems thinking, integrating both social science and ecological data (e.g. Checkland 1991; Therivel, Wilson et al. 1992; Naveh and Lieberman 1994; De Marchi, Funtowicz et al. 2000; Kidd 2000; Prato 2000; Rijsberman and van de Ven 2000). An epistemological framework based on embodied realism (e.g. Varela, Thompson et al. 1991; Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Sinha and Jensen De Lo  Pez 2000; Steen 2000) provides a dialectic bridge between an interpretative, grounded approach and a framework of commonly agreed principles of sustainability based on ecology. The concepts of emergent properties (context dependency, emergence from interactions, novelty and adaptation), generative structures (adapted, self-maintaining structures and patterns which can be replicated) and liminality (process of change, betwixt and between, recombination) (Turner 1985) are key to this epistemology (e.g. Bertalanffy 1968; de Rosnay 1975; Rappaport 1976; Capra 1982; Checkland 1991; Kay, Regier et al. 1999; Hellström, Jeppsson et al. 2000).

There are three phases in the research process. The first two phases involve an investigation of the Mersey Basin Campaign, and thus are by nature case studies. The Campaign as a whole will be investigated from the perspective of partnership networking and strategic planning across multiple scales. The second phase will follow a similar format, focusing in more depth on the River Valley Initiatives (RVI), a major mechanism for delivering strategic principles at the local and sub-regional scale within the Campaign (Kidd and Shaw 2000). This will set the context and provide essential information for interpretation in the third, and major phase of the research. In this phase of action based research, the researcher will facilitate a participatory planning and design process in a RVI (appropriate case study to be identified during the second phase of research).

The overall methodological strategy for the research is a qualitative, interpretative approach, aiming to delve further into key areas that have been identified by previous reviews of the Campaign (Wood, Handley et al. 1997; Wood, Handley et al. 1999; Kidd and Shaw 2000) and the literature on Integrated Catchment Management (e.g. Carnie 1994; Carpenter 1999; Sophocleous 2000, Steiner, Blair, et al. 2000, Van Straaten 1995; Verheem 2000; Verniers and Lens 1995) and Sustainable Planning (e.g. Baschak and Brown 1995; Boothby 2000; Carr 1998; Forman 1998; Lewis 1996; Linehan and Gross 1998; Lyle 1994).

Data will be coded in an inductive process. The overall view of the stakeholders and processes will be modelled using soft systems approaches. The sampling strategy is theoretical, in that processes and interviewees will be chosen due to their relevance to the conceptual framework and research questions. In response to much recent writing on the importance of considering different levels of scale in research into complex systems (Gibson, Ostrom et al. 2000)[2], the methodology seeks to create a dynamic dialectic between a large scale overview and detailed contextual information to provide depth and a grounded interpretation of actor’s perceptions.

An in-depth, qualitative approach is appropriate at this stage because there are few examples of creative participatory design approaches. The emphasis of the research question is on the process of design and communication. This requires a particular focus on participants' perceptions and reactions to the design process.

As much of the research into sustainable development is responding to a relatively new imperative and new approaches, it is by its nature often action research, or research in which there is intervention in a system through the agency of the research project. Similar to research into information systems, where the research focus is on a ‘newly invented technique’, action research may be a necessary approach (Baskerville and Wood-Harper 1996, pg. 240) for studying integrated sustainable planning. Action research offers a bridge between tools for investigating social life, such as naturalistic inquiry, and making effective use of the knowledge gained in applied projects (Reason, 1994, Stringer, 1999).

This methodological focus was chosen in response to the nature of the research problems and epistemological issues raised in the literature on sustainable development about the need for interdisciplinary, multi-scaled, systems approaches. It stems from an ontological position that meaning is a socially constructed concept, but that the conditions for the construction of thought and meaning are framed by biological functioning and ecological conditions, which have common, shared characteristics, and are vital for continued health of society and individuals. The methodology chosen is consistent with the epistemological underpinnings of the design tool under research, which stems from the researcher's professional experience working with the issues of sustainable development.

Research Questions, Methods and Sampling Strategy

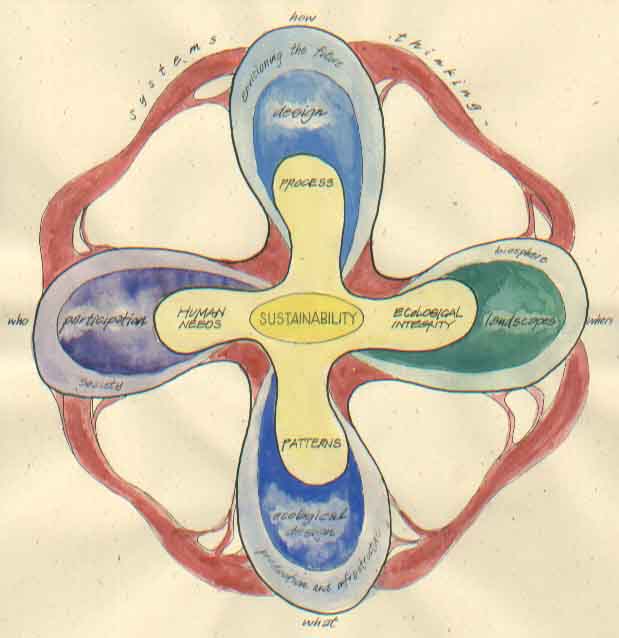

The literature review has highlighted 5 areas of importance to the overall research question of sustainable planning. These are:

· Systems Thinking

· Design

· Participation

· Landscapes

· Ecological Design

The detailed research questions are organised around these themes. The conceptual framework can be summarised in Figure 1:

Figure

1: Conceptual Framework of Research

Phase One: The Mersey Basin Campaign - A mechanism for sustainable planning?

The aim of this research is to gain an overview of the Campaign’s structure and mechanisms from the point of view of partnership structures and integrated sustainability principles. This will delve further into two delivery mechanisms of the Campaign’s approach, partnership networking and strategic linking across multiple scales, which have been identified both by the Campaign (Corporate Plan 2001) and in reviews of the Campaign (Wood, 1999; Kidd, 2000; Wood, 1997).

Research Question:

How does the MBC structure work as a

tool for delivering planning for sustainability?

This poses three inter-related questions:

- What are the characteristics of the process of communication and co-ordination within MBC that help to increase partnership and cross-sectoral working?

- How is strategic, holistic thinking encouraged at multiple scales in the partnerships within MBC?

- What is MBC's understanding of 'ecological design' in relation to the aims and objective of the organisation?

Outcomes

- Principles for successful implementation/development of MBC concept in different contexts – the basis for information packages (to be developed by MBC) both for internal use and for other organisations wishing to learn from the Campaign

- A systems modelling of the overall structure of the Campaign and processes that encourage cross-sectoral communication and strategic planning at multiple scales

Note: this is not intended as an assessment of the effectiveness of the MBC as a tool for delivering planning for sustainability, rather as an inquiry into the processes that facilitate the key areas and actions that have already been highlighted by previous research. A thorough assessment of the effectiveness of the Campaign is beyond the scope of this project.

Sampling Strategy

This research project will look at the MBC as a whole, and thus needs to include some work on each of the major sectors and areas of work. This will lead to decision of which RVI for action based research – this can then be studied in more depth in Nov/Dec. after MA thesis is handed in (second phase of this aspect of the research project). At this stage in the research, key stakeholders and players will be interviewed.

Two important characteristics of MBC identified in the literature are: the co-ordination of a strategic, large scale approach with local actions and stakeholder stewardship of projects and facilitating cross-sectoral partnerships. Thus key axes for sampling are to look at different levels of scale and different sectors.

Methods

Interviews of key stakeholders and actors

Participant Observation of Processes and events, e.g.:

- Steering meeting of RVI

- Training new RVI co-ordinator

- Community events

- Envisioning events

- Steering group meeting

Review of Campaign literature, e.g.:

- Project plans

- Project materials (e.g. educational packs, communication tools)

- Official documentation

- River Valley Action Information (co-ordination across RVIs)

- RVI Study and Action Plans

- Minutes of meetings

- Training materials for co-ordinators

Analysis techniques

· Inductive coding of participant’s perceptions (important grounding of ideas in order to provide a good base point for further study)

· Systems modelling of processes and principles

Draft Questions:

The following questions are a draft set of questions for the interviews and to guide the reading of documentation and participant observation, intended to answer the overall research questions:

|

Topic |

Interview

Questions (DRAFT) |

|

Sustainable Planning – Design and Management |

How is design orientation and futures

thinking encouraged in the MBC? How is creative cross-sectoral thinking

encouraged in MBC activities? What is the conceptual framework for

management? What are the mechanisms for creating

strategic overview – what are the channels, processes, principles used? How

are new partners brought into the process? How is this updated over time? How is strategic view translated to other

activities and levels of scale? What are the generic common, principles,

and what is contextually driven? How are the goals and objectives of

partnership organisations integrated with the overall aims of the Campaign? What criteria for sustainability are used? How are the 3 E’s of sustainability

practically incorporated into the decision-making processes? |

|

Participation |

How is the federalism concept encouraged? How is the concept of value adding for each

partner through the MBC activities encouraged? What are the processes and mechanisms used

to facilitate: Communication (activities, environmental change and challenges, decision

making, organisational structure) both within MBC and with partners. Education (role of partnership, value of, problems with, process and

structure, balance between education and coercion (Wood, 1999, pg. 349) Decision-making and the role of consensus – mechanism, limitations. Co-ordination

of activities and conflict resolution – how are

areas of disagreement negotiated? What ethical frameworks are used in

decision-making – to what extent are the values and goals of the

participating partners incorporated into the overall strategy and goals of

the MBC? To what extent are these made implicit and a focus of discussion? How is data gathered, stored and

co-ordinated – e.g. tools, access, educational materials, access to research

data, technologies (e.g. GIS, WWW, common data bases) What is the range of participation – social

exclusion relationship? |

|

Ecological Design |

What role does thinking of long-term

ecological infrastructure; industrial ecology, green building, sustainable

agriculture (urban and rural), mixed used forestry and ecological restoration

play in activities? What design principles and processes are

used? |

|

Landscapes |

How is holistic, integrated science

understood, used, disseminated/taught? How are the links between water quality,

land use patterns, soil use, material and energy flows and air pollution

discussed and integrated into the planning process? How does the River Region concept help to

create a sense of region in practice? |

|

Systems Thinking |

What underlying principles and theories

inform thinking and policy in MBC? |

Phase Two: The River

Valley Initiatives - A mechanism for linking strategic objectives and local

actions?

The role of the RVIs as a mechanism for delivering the aims of the Campaign will be investigated. The use of ecological design principles within Campaign and partners’ projects will also be explored. A further aim of this phase of the research is to verify the appropriate level of scale and mechanism for the action based phase of the research into a participatory protocol for ecologically informed design and planning. Ecological and social data relevant to the action based research will be collected for a desk study of the area in preparation for the action based phase. The methods, data sources and analysis will be similar to the first phase.

RVI – Case study criteria

Could be typical, exemplary, problematic (same issues for action based part of research - to what extent should these mirror each other?)

Have some design and participatory planning work already ongoing?

Should it be the same RVI as the site chosen for the action research?

Sampling strategy

Theoretical sampling should determine who amongst the participants in the research process should be included in the research in more depth. The sampling strategy would ideally include a similar range (sector, type of activity, scale of operation) as for the MA research. The main difference would be that there are more likely to be people mainly concerned with the local (RVI) level of scale, though it would be advantageous to interview at least one person who acts as a link to the strategic catchment wide level of scale. This would include a focus on small businesses and local employees. At this stage, findings from the first stage of research will be triangulated through an investigation of the perceptions of community members and people at different levels in the MBC partnership organisations.

Phase Three: Testing the

DesignWays Process in a River

Valley Initiative

The chart in appendix A provides the beginning of clarifying the research questions and possible means of assessing the questions in the action based phase of the research. The scope is still too broad, but at this stage it is helpful to look at the whole of what could be asked in this phase of the research. It is envisaged that the Masters project will act as a scoping exercise and the second phase of the PhD research will provide a theoretical framework for narrowing the questions down. The methodology will be further formulated with reference to action based research such as Darling-Hammond and Snyder's (2000) assessment of teaching practices.

Criteria for choice of RVI for action research

The key concern for choice of RVI site, according to the RVI Manager, is to pick a site where there is high enthusiasm and a fairly well functioning group (the RVIs vary considerably in this respect). As this is a pilot project and will take a fair commitment, it will be practically necessary to choose a site with a high degree of support for the project from the RVI co-ordinator.

It would be preferable if the area already has a lot of landscape ecology data – (less primary data gathering of that nature for me to do – take it as a given that the design process fits in with this and hopefully also adds to it). It would also be advantageous if the area has potential for industrial development (e.g. Groundwork eco- industrial cluster pilot project).

Includes:

· Derelict land

· Common land

· Agriculture

· Maybe includes a new development of housing coming up.

· Possibly a school

· Could include several smaller projects that can be linked through the design process, e.g. the current derelict land regeneration process being piloted by MBC

Sampling strategy and numbers of participants in action based research

Ideally, the participants in research would represent a broad range of stakeholders, similar to those interviewed in the second phase of research.

15 - 25 people or so involved in design process on an ongoing basis (more in some sessions possible)

Up to 100 attend some workshops and visioning (with extra support from MBC)?

5 –6 more in-depth informants from the larger group?

Criteria for assessment of research

“The fundamental challenge of the sociological

endeavour today must be to develop (objective) useful knowledge of the complex

gamut of everyday life, from unspoken exchanges of love…. To systematic

planning and construction of new societies – and a new world order in which

pluralistic differences are balanced against universal orderings. To do this we

must always being with the members’ understandings of their situations, but as

we increase our understanding we must seek to transcend the members’

understandings to create transsituational (objective) knowledge” (Douglas, 1971 #997, pg. 44, quoted

in Blaikie 1993, pg. 185)

Criteria for assessing this research are of particular importance due to the fact that the researcher is also the originator of the design process under study and will be facilitating the action based phase of the research. Paying attention to criteria for assessment will help to decrease the possibility of bias in the analysis of project data. To be consistent with the epistemological underpinnings of the research project, however, attention must also be paid to issues of social construction of meaning and the purpose and values of the research (Schwandt 2000).

The literature on research into complex eco-social systems increasingly stresses the importance of stakeholders' goals in defining a valid research goal. This will in turn lead to a different concept of assessment of research output, which may be best assessed not on popularity in academic literature, but on the impact they have on the planning and management of landscapes and the effect that they have on behaviour towards and perception of this management in the participating stakeholders (Roe 2000; Hobbs 1997; Linehan and Gross 1998). Post normal science (an important theoretical underpinning of this research project) holds that the criteria of usefulness and relevance to policy are important criteria of research quality (Tacconi 1998; Tognetti 1999).

Much of the assessment of systems thinking in research has been pragmatic, and has attempted to evaluate the use of the concepts as a heuristic tool, developing criteria for evaluation in the light of research context and goals of the participants. Achieving goals and participant satisfaction may act as valuable criteria for evaluation “Ex-post satisfaction is related to the well-known criterion of achieving win-win situations, which is sometimes also proposed for judging the outcomes of negotiations in networks” (Thissen 2000, pg. 121).

Lincoln and Guba (2000, pg. 180 - 181) promote three criteria for authenticity in research: fairness, a ‘quality of balance’, in which all stakeholders’ are taken into account and reflected in the research narrative, ontological and educative authenticity, which incorporates a ‘raised level of awareness’ and catalytic and tactical authenticities, in which an inquiry is capable of promoting action in participants, and the researchers are capable of providing training in specific forms of social action if it is required. Such criteria will be useful in considering an action based research project with community members. However, it should be born in mind that criteria of usefulness of research can be problematic – immediate usefulness of research may not be apparent, sometimes research is not immediately useful in the context in which it is carried out, but proves to have use for another context or at a later date. It could be limiting to use this criteria for quality of research.

In the emerging discipline of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), three classes of evaluation criteria have been discussed – input, process and outputs.

“Inputs are factors like resource and time

constraints, data and theory availability, given problem formulations, quality

of analysts and the like. Process characteristics include methodology adopted,

degree of formalisation of analytic activities, knowledge utilization,

attention to documentation, adherence to procedural rules, collaboration with

users, and the like. Output characteristics for evaluation include, among

others, quality and robustness of conclusions, clarity and accessibility of

reports, matching with the issues and needs of the users, and the use of study

results” (Thissen 2000, pg. 119).

In this research project, the focus

may be on the process criteria, with some focus on the output data, e.g.

evaluation of plans and peer review of project (see Appendix A for sketch of

possible assessment criteria).

Denzin (2000, pg. 886) states that “inquiry [can be recognised] as a social process in which we construct reality as we go along, as a social process in which we, at one and the same time, construct our criteria for judging inquiries”. This implies that the criteria for assessing the research may need to be developed in response to the findings of each phase of the research, as well as in relationship to the pragmatic use that participants are able to make of the findings.

Sources of data to answer research questions

Note: details of what could be assessed for this research project are laid out in Appendix A. it is not envisaged that all of the possibilities in that chart will end up in the final research project.

Similar to recent research evaluating Integrated Estuary plans (Roe 2000) I would suggest that in an ideal research project looking at large scale sustainability issues, assessment needs to focus on several levels of change, which are separated in time as well as in arena of action. The first is in the perception and attitudes of the participants. This can be assessed during and immediately following a project. The second is in terms of the behavioural shifts that are observed to occur (possibly as a result of these perceptual shifts or as a result of the research or program intervention). Developing valid criteria for assessment may be part of the research design, and even of the evaluation of perceptual shifts (e.g. criteria based in the perceptions and values of the participants in the light of the research context). The third level is possibly more easily quantified and related to a natural science framework, measuring the actual ecological effects of the actions.

This third level, of substantive effects in the environment, is however, not a simple problem of measuring precisely ecological parameters and being able to relate these directly to the research or project intervention, as there are many potential effects on the ecological health of a system, which may come from outside the boundaries of the system (e.g. trans-regional air pollution), and there could be other factors affecting the ecological parameters that are not necessarily related to the behavioural shifts resulting from the particular project (e.g. shifts in regulations concerning pollution outfalls). However, the problematic nature of causal effects in complex dynamic systems does not mean that it is not a necessary part of research into sustainability issues to look at aspects of environmental quality, and whether or not they are in fact improving. This may necessitate ecological baseline measurements, so that ecological parameters can be assessed and any changes can be compared to the state of the local environment before the research intervention.

These issues will be of increasing interest in the MBC. Water quality in the Mersey Basin has seen dramatic improvement over the first 15 years of the Campaign. Much of this improvement may be attributable to fairly large scale engineering interventions- such as the creating an interception sewage tunnel for Liverpool, and major increases in end-of-pipe control of pollution at several large industrial sites. The next phase of the Campaign (which is currently under discussion) will involve focussing on non-point sources of pollution, domestic, agricultural and land use effects on water quality and the character of waterside environments. These concerns are more complex in nature and more difficult to monitor. They also require more fundamental behavioural shifts, which will be related to shifts in perception about the nature of people’s everyday actions on the environment and water quality in the area. It is in this context that the DesignWays process may be particularly valuable, but it is a context which defies simple casual relationships and measurers of environmental quality as an indicator of success.

In addition, due to the fact that there is a 3-year limit on this research project, it will not be possible to measure substantive areas of outcome from the project. There will not have been time for design projects to be implemented and thus assessed for practical outcomes. Ideally the types of ecological change that could be measures should be discussed, and may develop into a complimentary research project.

Analysis techniques

Participant perceptions

With reference to people’s perceptions of rules and principles as a guidelines for behaviour, ethnomethodology has an objective of describing the way in which “recognizable structures of observable behaviour, systems of motivation, or casual ties between motivations and patterns of behavior – is made visible thorough members’ descriptive and accounting practices” (Holstein and Gubrium 1994, pg. 264). However, as the focus is on “competencies that underlie ordinary social activities” (Holstein and Gubrium 1994, pg. 265), this may be a difficult method to use in this study, in which much interaction between researcher and ‘research participants’ will not be in day to day working in the community or jobs, but in a ‘framed’, out-of-everyday context situations of workshops and design meetings.

However, Holstein (1994) suggests that there is a potential for interpretation with “ethnomethodological sensibility’ which can help to link micro and macro areas of discourse, which is a concern of this research project.

‘Post-analytic’ ethnomethodology focuses on the way in which people construct work practices, with studies focusing on “the embodied conceptualizations and practices that practitioners within a particular domain of work recognize as belonging to that domain” (Holstein and Gubrium 1994, pg. 266). This may prove a fruitful area of inquiry for a way of understanding principles of Integrated Catchment Management and stakeholder partnerships within MBC. However, this approach discourages the creation of comprehensive frameworks, rather focusing on specific practices bounded in a specific situation, which does not sit well with the more retroductive systems modelling approach that this research methodology is based on.

It may be worth looking into the possibility of an observational role of more day-to-day activities during the research process, though this may be sufficiently dealt with in the MA research and in the follow on more detailed research for the selected RVI.

Though this research project is not following a grounded theory methodology, it will employ many of the techniques of grounded theory in analysis, in particular the coding of participant’s perceptions from data gathered in interviews, focus groups and from participant observation (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Strauss and Corbin 1994; Charmaz 2000). This inductive coding is seen as a necessary complement to the systems modelling and overviews of the theoretical framework and as a means of decreasing the researcher’s bias in the process. The concept of theoretical sampling will also be employed throughout the research process.

Metaphorical modelling

Several works in qualitative research methodology (Miles and Huberman 1994; Darling-Hammond and Snyder 2000; Janesick 2000) (Richardson 2000) mention the importance of looking at metaphorical constructs in interpretation, and some research work explicitly looks at an active engagement of metaphorical construction in reasoning, in particular through the concept of retroductive reasoning explored by Blaikie (1993), and the concepts of imaginative modelling espoused in soft systems methodology (Checkland 1991). Participatory research, looking at the concept of diagramming participant’s concepts and illuminating metaphors of concepts, has proved fruitful in research into topics as diverse as primary school education and the effectiveness of teaching in the UK (Darling-Hammond and Snyder 2000) and sex education for Aids awareness in rural Zimbabwe (Kesby 2000). Attention to these types of interpretation is consistent with the epistemological underpinning of this research project.

Reflexivity

Turner (1985, pg. 181) has explained reflexivity as "the ability to communicate about the communication system itself". Attention to reflexive questioning will be of particular importance in this research project. In addition to the coding of participant’s perceptions, the possibility of a peer review assessment, two further techniques will help to increase the reflexive attention of the researcher. Workshops will be held in order to allow participants in the research process the opportunity to test and comment on the researcher’s analysis. During the action based phase, the researcher will maintain a reflexive journal, tracking progress and role in research (Janesick 2000).

Ethical considerations

Who is participating – range, representative – gender, race, economic status, special interests, etc. (Christians 2000)?

Who isn’t and why not?

How inclusive?

Possibility of legitimating existing powers, structures and actions

Raising hopes that the design will be implemented or will affect policy, when this may not be the case, or there are no mechanisms in place to do so at the moment

How I interpret and represent findings may have an effect on MBC and partnership organisations, policy, programs of further development e.g. in 2/3 World, there could be a lot of money riding on this.

How possible is a fundamental critique of capitalism from a sustainability perspective within a business stakeholder partnership?

In an era of increased corporate funding of higher education, we may well see the “the progressive merging of cultural pedagogy and the productive processes within advanced capitalism. Although, as researchers, we may not be interested in global capitalism, we can be sure that it is interested in us” (Kinechloe and McLaren 2000, pg. 304).

Goffman’s concept for obtaining research data in an organisation is that you should start at the bottom and work up in power structures in order to have a better chance of finding out what people ‘really’ think – how does this work in terms of having the Chief Executive as my supervisor, and going through him for contacts? What happens if my idea of what is important and his contradict each other?

In looking at sustainability issues – research can affect jobs, trade, fair trade issues, environmental justice, concepts and practices of equity.

Research

Validity

“Was it new for anything in this world to be

unequal, inconsistent, incongruous – or for chance and circumstances (as second

causes) to direct the human fate?” (Emma, Jane Austen)

Funtowitz and Ravetz suggest that a positivist focus on truth in research can be replaced by a concept of Quality. This quality requires that values and assumptions in the research are made explicit, that scientific argument is based not on “formalized deduction but on interactive dialogue” and the concept of peer review should be broadened to include a wider range of stakeholders and participation in the research process (Tacconi 1998, pg. 98). The attempts to increase reflexivity and include participants in the generation and interpretation of data may go some way towards this concept of research quality, and help to deal with some of the threats to validity which stem from such a complex and wide ranging research project.

It may be possible to increase validity of research results by using a ‘control group’ by looking at another, similar project being undertaken which does not use the Pathway process. It may be possible to look at one of the derelict land cluster schemes and interview some the people involved in this scheme.

Contextual information

To what extent is it possible/necessary to also look at the larger context of the project and to consider ways in which this might affect assessment of the design process – e.g. political context – regulations, planning guidance, similar projects in the area – e.g. LA21, regional context e.g. AFS, funding issues for projects (play a role in implementation) ownership issues, e.g. water rights, land ownership, interaction of utilities. In the first phase, I will be interviewing the head of Sustainability North West and the Sustainability co-ordinator for Action For Sustainability, the regional framework for sustainable development in the North West (NWRA and GONW 2000). This should give an improved indication as to how to deal with these issues in the major phases of the research.

Alternative explanations

Instead of any result springing from the DesignWays process, they may spring from the time taken and the fact that people get together with the purpose of thinking about the future?

One way to deal with this is to do a design exercise at an early stage in the process, before the design process kicks in – this would allow for participants to reflect on what they learned from the design process. As this would be quite a short ‘struggle’ exercise, there is not a clear basis for comparison for the design done with and without the design process (the shorter period of time spent on the exercise would necessarily mean that the design does not have the same depth as the one produced from the DesignWays process), but as an exercise it will give participants a fruitful point of comparison. How did they respond to doing a design exercise without a clear process? What difference did the DesignWays process make? This is particularly important in a circumstance where many of the participants may not have been involved in design or planning projects before, and thus do not have an experiential basis for comparing the DesignWays process to any other process.

The logic of the Masters thesis – How does the MBC structure work as a tool for facilitating sustainability planning – can also be seen as a useful basis for comparison, as this will look at the activities of the MBC (Including RVIs) without the DesignWays process. It may be useful to carry out a more in-depth case study on the RVI that is chosen for the action based part of the research in the second phase of the case study, before carrying out the DesignWays process. This would provide further data for comparison (before and after).

Maturation - The action of the MBC is bearing fruit – more people are aware and involved and results of the research project stem from this cause.

Other programs and projects in the area affect people’s perceptions and actions. E.g. LA21, Action for Sustainability.

Other factors that could account for changes include:

· Increase in awareness – education, media campaigns, and environmental disasters that get extensive media coverage.

· Regulations/laws change

· Actions ‘upstream’ increase or decrease pollutant loadings - e.g. new factory, sewer pipes built, increase of market gardening in area.

· Larger scale catastrophe changes environmental conditions e.g. flooding.

· Economic changes affect behaviour – e.g. Petrol prices rise.

· Nothing is implemented due to lack of political support, sabotage from special interests, lack of funding, other shifts in area e.g. increase in unemployment.

Generic participation issues:

· Transience of population – it is hard to identity with landscape.

· Stakeholderitis – overload of participation leading to less enthusiasm and involvement.

· Only activists or NIMBY’s come to the design process meetings.

· Facilitator involvement – people like/dislike interacting with me as a person and this skews the results.

Potential

Problems with Research

The problems that are likely to be encountered during this research stem from practical and methodological considerations. The challenge in conducting research into complex systems is one of finding a balance between breadth and depth. In this instance there are many players and factors operating across several levels of scale and in many different geographic and administrative areas. The interdisciplinary nature of the research poses the difficulty of synthesising concepts and data from diverse fields. The nature of the research questions increases the breadth of possible data sources and research questions. It is difficult to draw a line around the scope and depth of the potential participants in the research process.

There are many advantages of collaborative research between public institutions and academia (Archer and Whitaker 1994), but there are also several difficulties. The fact that this research is funded in part by the Campaign, a body funded from many sources, and many respondents are either employees of MBC or work for partner statutory bodies, may pose questions of confidentiality and difficulty in eliciting a critical response from interviewees. There is also the potential for pressure from the research partner to produce results rapidly. In terms of the methodology, the research partner has made a concerted shift towards quantitative assessment of their activities over the last several years, and an interpretive, qualitative research report may not fit well within the current corporate focus.

In the action based phase, the difficulties will include accessing sufficient time and resources to carry out the design process, which is a time consuming process in and of itself. Engaging in the design process may be suggesting that the design concepts will be implemented, while the research project has no such jurisdiction, authority or resources. Careful communication about what will actually be possible is required.

Several other practical considerations may impact the research process. Participants may leave part way through. People may come in and out of the process as their schedules change, which is problematic both for the design process and building of a working group and the consistency of research results – people’s perceptions of the process may vary widely due to the amount they have attended the process, especially if they have missed the introductions or key sessions.

The fact that the researcher is also the originator of the design process and will be facilitating the action based research phase will require particular attention to questions of objectivity and bias in research. This increases the need for triangulation of data, reflexive study and particular attention to participants’ interpretation. A peer review process may form an essential part of the data gathering.

Weaknesses in research design

· Too complex – unmanageable

· Many factors of irreducible uncertainty

· Too many variables, hard to distinguish and verify correlations

· Lack of depth in any one area (except sustainable design process)

· Too many research questions (these will be narrowed down)

· Lack of easy to measure criteria of success

· Could be a cyclical argument between research process and findings – you are bound to find what you are looking for if you ask questions in this way

· Not a clear distinction between interpretive methodology and systems modelling?

· Potential ‘researcher as facilitator’ effect on reliability

Unanswered questions

How does a California case study fit into the research focus? Determine what is unique about MBC? Helps set context for design?

Does this attempt at a coherent methodology seem fruitful? Could it be open to an accusation of circular logic – solving puzzles using own criteria, bound to find out what you want to because of how you are asking the question, or is the methodological and data source triangulation sufficient? An example of this issue is discussed in Bushe and Coetzer's (1995) study into appreciative inquiry as a team building tool, in which they used positivist objectivist research methods to investigate a research tool which has deeply constructionist epistemological underpinnings.

References

Archer, L. and D.

Whitaker (1994). Developing a Culture of Learning Through Research

Partnerships. Participation In Human Inquiry. P. Reason. London, Sage

Publications: 163 - 186.

Baschak, L. A. and R. D. Brown (1995). “An ecological framework for the

planning, design and management of urban river greenways.” Landscape and

Urban Planning(33): 211 - 225.

Baskerville, R., L. and T. A. Wood-Harper (1996). “A critical

perspective on action research as a method for information systems research.” Journal

of Information Technology(11): 235 - 246.

Bertalanffy, L. V. (1968). General System Theory. New York,

Braziller.

Blaikie, N. (1993). Approaches to Social Enquiry. Cambridge

(UK), Polity Press.

Boothby, J. (2000). “An Ecological Focus for Landscape Planning.” Landscape

Research 25(3): 281 - 289.

Bushe, G. R. and G. Coetzer (1995). “Appreciative inquiry as a

team-development intervention: A controlled experiment.” Journal of Applied

Behavioral Science 31(1): 13 -

31.

Capra, F. (1982). The turning point:science, society, and the rising

culture. New York, Simon and Schuster.

Carnie, C. G. (1994). Salmon in the river basin. Integrated River

Basin Development. C. Kirby and W. R. White. Chichester, John Wiley and

Sons: 437 - 445.

Carpenter, R. (1999). “Keep EIA Focused.” Environmental Impact

Assessment Review(19): 111 - 112.

Carr, A. J. P. (1998). “Choctaw Eco-Industrial park: an ecological

approach to industrial land use planning and design.” Landscape and Urban

Planning(42): 239 - 257.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded Theory - Objectivist and Constructivist

Methods. Handbook of Qualitative Research, Second Edition. N. K. Denzin

and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications: 509 - 535.

Checkland, P. (1991). Systems

Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester, John Wiley and Sons.

Christians, C. G. (2000).

Ethics and Politics in Qualitative Research. Handbook of Qualitative

Research, Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks,

Sage Publications: 133 - 155.

Darier, E., Gough, C., B.

Marchi, et al. (1999). “Between Democracy and Expertise? Citizens'

Participation and Environmental Integrated Assessment in Venice (Italy) and St.

Helens (UK).” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning(1): 103 -120.

Darling-Hammond, L. and J.

Snyder (2000). “Authentic assessment of teaching in context.” Teaching and

Teacher Education 16(5 - 6): 523

- 545.

De Marchi, B., S. O.

Funtowicz, et al. (2000). “Combining participative and institutional approaches

with multicriteria evaluation. An empirical study for water issues in Troina,

Sicily.” Ecological Economics(34): 267 -282.

de Rosnay, J. (1975). Macroscope

- a New World Scientific System. Publishers, Harper & Row.

Denzin, N. K. (2000). The

Practices and Politics of Interpretation. Handbook of Qualitative Research,

Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Sage

Publications: 897 - 922.

European

Union, The European Parliament The Council, Luxembourg, 23 October 2000,

Directive Of The European Parliament And Of The Council 2000/60/Ec,

Establishing A Framework For Community Action In The Field Of Water Policy.

Forman, R. T. T. (1998). Land Mosaics, The Ecology of Landscapes and

Regions. Cambridge (UK), Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, C. C., E. Ostrom, et

al. (2000). “The concept of scale and the human dimensions of global change: a

survey.” Ecological Economics(32): 217 - 239.

Hawken, P., A. Lovins, et

al. (1999). Natural Capitalism. Boston, Little Brown and Company.

Hellström, D., U. Jeppsson,

et al. (2000). “A framework for systems analysis of sustainable urban water

management.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 20(3): 311-321.

Hobbs, R. (1997). “Future

landscapes and the future of landscape ecology.” Landscape and Urban

Planning(37): 1 - 9.

Holstein, J. A. and J. F.

Gubrium (1994). Phenomemology, Ethnomethodology, and Interpretive Practice. Handbook

of Qualitative Research. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks,

Sage Publications: 262 - 272.

Janesick, V. J. (2000). The

Choreography of Qualitative Research Design. Handbook of Qualitative

Research, Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks,

Sage Publications: 379 - 399.

Kay, j. J., H. A. Regier, et

al. (1999). “An ecosystem approach for sustainability: addressing the challenge

of complexity.” Futures(31): 721 - 742.

Kidd, S. (2000). “Landscape

Planning at the Regional Scale: an example from North West England.” Landscape

Research 25(3): 355 - 364.

Kidd, S. and D. Shaw (2000).

“The Mersey Basin and its River Valley Initiatives: an appropriate model for

the management of rivers?” Local Environment 5(2): 191 - 209.

Kinechloe, J. L. and P.

McLaren (2000). Rethinking Critical Theory and Qualitative Research. Handbook

of Qualitative Research, Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln.

Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications: 279

- 313.

Kesby, M. (2000). “Participatory diagramming as a means to improve

communication about sex in rural Zimbabwe: a pilot study.” Social Science

& Medicine 50(12):

1723-1741.

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson

(1980). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson

(1999). Philosophy in the Flesh, The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to

Western Thought. New York, Basic Books.

Lewis, P. H. (1996). Tomorrow

by Design, Regional Design Process for Sustainability. New York, John Wiley

and Sons.

Lincoln, Y. S. and G. E. G.

(2000). Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences. Handbook

of Qualitative Research, Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln.

Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications: 163

- 188.

Linehan, J. R. and M. Gross

(1998). “Back to the future, back to basics: the social ecology of landscapes

and the future of landscape planning.” Landscape and Urban Planning(42).

Luz, F. (2000).

“Participatory landscape ecology - A basis for acceptance and implementation.” Landscape

and Urban Planning 50: 157-166.

Lyle, J. T. (1994). Regenerative

Design for Sustainable Development. New York, John Wiley and Sons.

Miles, M. B. and A. M.

Huberman (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis - An Expanded Sourcebook Second

Edition. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Naveh, Z. and A. S.

Lieberman (1994). Landscape Ecology Theory and Applications. New York,

Springer.

NWRA and GONW (2000). Action

for Sustainability. North West Regional Assembly and Government Office of the

North West.

Prato, T. (2000). “Multiple

attribute evaluation of landscape management.” Journal of Environmental

Management(60): 325 - 337.

Rappaport, A. (1976).

“General Systems Theory, A Bridge Between Two Cultures (3rd Annual Ludwig von

Bertalanaffy Memorial Lecture).” Behavioral Science(21): 228 - 239.

Reason, P. (1994). Human

Inquiry as Discipline and Practice. Participation In Human Inquiry. P.

Reason. London, Sage Publications: 40

- 56.

Richardson, L. (2000).

Writing - A Method of Inquiry. Handbook of Qualitative Research, Second

Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications: 923 - 948.

Rijsberman, M. A. and F. H.

M. van de Ven (2000). “Different approaches to assessment of design and

management of sustainable urban water systems.” Environmental Impact

Assessment Review(20): 333 - 345.

Roe, M. (2000). “Landscape

planning for sustainability: community participation in estuary management

plans.” Landscape Research 25(2):

157 - 182.

Schwandt, T. A. (2000).

Three Epistemological Stances for Qualitative Inquiry - Interpretivism,

Hermeneutics and Social Constructivism. Handbook of Qualitative Research,

Second Edition. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Sage

Publications: 189 - 213.

Sinha, C. and K. Jensen De

Lo  Pez (2000). “Language, culture and the embodiment of spatial cognition.” Cognitive

Linguistics 11(1-2): 17 -41.

Sophocleous, M. (2000). “From safe yield to sustainable development of

water resources - the Kansas experience.” Journal of Hydrology(235): 27

- 43.

Steen, F. F. (2000).

“Grasping Philosophy by the Roots.” Philosophy and Literature 24(1): 197-203.

Steiner, F., J. Blair, et al. (2000). “A watershed at a watershed: the

potential for environmentally sensitive area protection in the upper San Pedro

Drainage Basin (Mexico and USA).” Landscape and Urban Planning(49): 129

- 148.

Strauss, A. and J. Corbin

(1990). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and

techniques. Newbury Park, Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. and J. Corbin

(1994). Grounded Theory Methodology - An Overview. Handbook of Qualitative

Research. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Tacconi, L. (1998).

“Scientific methodology for ecological economics.” Ecological Economics(27):

91-105.

Therivel, R., E. Wilson, et

al. (1992). Strategic Environmental Assessment. London, Earthscan

Publications.

Thissen, W. A. H. (2000).

Criteria for Evaluation of SEA. Perspectives on Strategic Environmental

Assessment. M. Partidario and R. Clark. Florida, Lewis Publishers.

Tognetti, S. S. (1999).

“Science in a double bind: Gregory Bateson and the origins of post normal

science.” Futures(31): 689-703.

Turner, V. (1985). On the

Edge of the Bush, Anthropology as Experience. Tucson, Arizona, University

of Arizona Press.

Van der Ryn, S. and S. Cowan

(1995). Ecological Design. Washington D.C., Island Press.

Van Straaten, D., K. Nagels, et al. (1995). Technical approaches to

strategic environmental assessment regarding integrated water management.

International Symposium on Environmental Impact Assessments in Water

Management, Bruges, Belgium, Group for Applied Ecology (GTE), Flemish

Environment Agency (VMM), Flemish Administration of Environment, Nature and

Land Use (AMINAL).

Varela, F., Thompson, et al.

(1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press.

Verheem, R. (2000). The Use of SEA and EIA in Decision Making on

Drinking Water Management and Production in the Netherlands. Perspectives on

Strategic Environmental Assessment. M. Partidario and R. Clark. Florida,

Lewis Publishers.

Verniers, G. and V. Lens

(1995). Methodological approach of rivers as landscape elements.

International Symposium on Environmental Impact Assessments in Water

Management, Bruges, Belgium, Group for Applied Ecology (GTE), Flemish

Environment Agency (VMM), Flemish Administration of Environment, Nature and

Land Use (AMINAL).

Wood, R., J. Handley, et al.

(1999). “Sustainable Development and Institutional Design: The Example of the

Mersey Basin Campaign.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management

42(3): 341-345.

Wood, R., J. Handley, et al. (1997). Mersey Basin Campaign - Mid Term Report - Building a healthier economy through a cleaner environment, Mersey Basin Campaign.