Research

Summary

|

Integrated Catchment Management and Planning for

Sustainability -The Case of the Mersey Basin Campaign |

School of Planning and Landscape,

University of Manchester

November 16, 2001

Context

It has become clear over the last two decades that effective water management can only occur when all of the problems that can affect water quality are addressed. Symptoms of water-related problems are often detected far from their sources. Efforts to improve the water environment are impeded by multiple authorities not working together and a lack of effective links between local actions and catchment-wide planning.

This research examined 'planning for sustainability' in river catchment management, with the Mersey Basin Campaign as the principal case study. The newly enacted European Union Water Framework Directive requires each Member State to produce an integrated management plan for every river basin. These plans must be formulated with a high degree of community and stakeholder involvement. The Mersey Basin Campaign offers a valuable case study in how to achieve this ambitious objective.

The Mersey Basin Campaign

The Mersey Basin Campaign, a 25-year government initiative launched by the Department of the Environment (UK) in 1985, is seen as an important player in achieving the North West region’s objective of a ‘green and pleasant region’ (NWRA 1993) . It was awarded the inaugural International RiverPrize for best practice in Catchment Management in Brisbane, Australia in 1999. This prize recognised its pioneering role in developing a stakeholder partnership for catchment-wide planning and action.

Situated

in the North West of the UK, the Mersey's 2000 kilometres of waterways and

canals hold significant historic value. Owing to their key role in the development

of the Industrial Revolution and subsequent industrial development, they also

offer a long-term case study in pollution and neglect of environmental assets.

The 4,680 km2 of the Basin are home to over 5 million people. The

Catchment includes areas of poverty and physical dereliction, as well as outstanding

natural beauty, such as the Peak District, and the cities of Manchester and

Liverpool. The Mersey was once described by Michael Heseltine (then Secretary

of State for the Environment “affront

to civilized society” (MBC

2000, pg. 2)

, and at the start of the Campaign, was the most polluted river in

the UK (Wood, Handley and Kidd

1997)

.

The Campaign's aims are:

·

Water Quality: to ensure that all rivers, streams and canals are of good quality

offering the cleanest possible litter free environment and diverse wildlife

habitat by 2015

·

Waterside Development: the Campaign partnership will operate directly and as a main strategic

player to stimulate the sustainable development of attractive waterside environments

– for businesses, housing, tourism, heritage, recreation and wildlife bringing

benefits to the regional economy

· Awareness and Education: create and support a culture to mark out the Mersey Basin as a region of waterways in which all who live and work cherish the waterside environment, understand it, take pride in the waterways & see the improvement as leading to a better quality of life (MBC 2001b)

In

order to achieve its aims, the MBC promotes basin-wide strategic planning

and local initiatives for long-term enhancement of the environment. It operates

as a flexible partnership, encouraging integrated work between the private

sector, communities and government bodies, and has been recognised as “a model for what will become an increasing need for engaging coordinated

action through a partnership approach” (Wood, Handley and Kidd 1999, pg. 342)

.

Research Project

This research has examined two of the Campaign’s delivery mechanisms identified as important in previous reviews of the Campaign, partnership networking and strategic planning, linking multiple geographical scales. Interviews with 25 key players, participant observation and programme literature provided a wealth of data.

The overall research question was:

How is ‘planning for sustainability’ delivered through the processes and mechanisms of the Mersey Basin Campaign?

This posed three inter-related questions:

1 What are the characteristics of communication and coordination within the Campaign that help to increase partnership and cross-sectoral working?

2 How is strategic planning encouraged at multiple scales in the partnerships within MBC?

3 How are sustainability principles applied in planning and projects?

Findings

The fact that water quality in the Mersey Basin has improved dramatically since the inception of the Campaign is a testament to its success. The research findings offer lessons from the 15 years of experience of the Campaign, which can be applied to similar initiatives, as well as pointers for improving the effectiveness of the Campaign itself. The findings are in three sections:

- Analysis

of the research questions

- Analysis

of the nature of partnerships and cross-cutting themes

- Conclusions

- Factors for successful Catchment-based partnerships

- Detailed

recommendations for the Campaign

These are summarised below.

Nature of partnerships

Benefits

- partnerships produce results beyond the capabilities of the individual entities

- cost effective way of working

· increased knowledge base for strategic planning

- enhanced possibilities for integrated thinking – combination of multiple perspectives

· broad range of support for projects

- behavioural change leading to sustained action

· long lasting benefits

- allowing participants to see how particular actions fit into a larger whole

· increased learning amongst participants

Disadvantages

· the work can seem an 'extra' duty

- possible

to shift responsibilities for doing work

Difficulties in setting up and maintaining

a partnership

- takes time to develop

- needs continuous maintenance and attention in order to remain viable

- difficult to maintain people’s enthusiasm over a long period of time

- both the partnership and external context change over time

- timetable of development needs to be driven by participants' needs rather than by the often rigid requirements of funding deadlines

- difficult to measure the added value brought by the partnership

- benefits tend to accrue in the longer term rather than immediately

- need to give credit to partners amongst whom the responsibilities are shared

Breakdown of Key Elements

of an Effective Partnership

|

Vision |

|

|

|

|

|

Structure |

|

|

|

Institutional· umbrella for broad engagement of sectors and stakeholders · equitable power sharing · transparent structure and decision making processes

|

|

|

|

|

Key Elements of an Effective Partnership (continued) Structure (continued) |

|

|

|

Spatial

|

|

|

|

|

|

Temporal

|

|

Process |

|

|

|

|

Quality

of Process

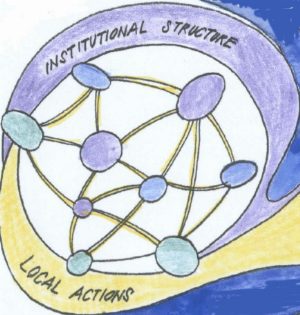

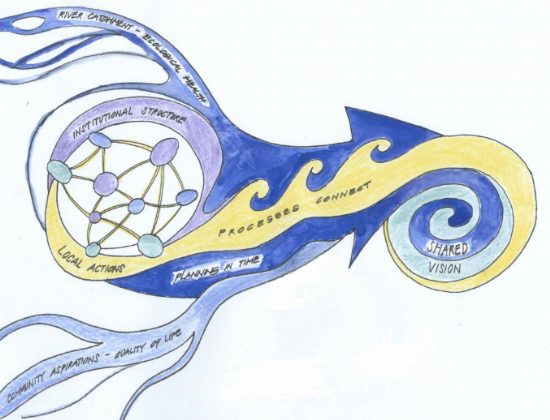

The processes involved in creating and maintaining a partnership play an important role in the success of the partnership. They provide a means of connecting the organisations in the partnership, local actions and the long-term vision. The difficulties encountered in developing a partnership can be better understood through an exploration of dualities and tensions inherent in a complex endeavour. Four key dualities that emerged from this analysis were:

- Importance of personalities and the need for systematic processes

· The need for meaningful participation and the pressure of limited time

· The need for long-term strategic planning and the pressure to meet short term targets

· The pressure for success stories and the possible danger of 'end of pipe' [2] solutions

There is a tension between the all-important building of relationships in a partnership and the need to systematize the networking process, so that the skills and knowledge vested in individuals is not lost to the partnership as those individuals change roles or leave the partnership. Whilst the benefits of increased participation in decision making are manifold, engaging meaningful participation is a time consuming process, and the benefits of this process tend to accrue in the long-term, which is problematic in a climate of increasing pressure for easily measurable short-term indicators of success. In some ways, the Campaign could be seen as a victim of its own success. Water quality improvements have been dramatic. The next phase of improvements, however, will involve behavioural change amongst a very broad range of water and land users, ranging from SMEs [3] to householders to farmers, as well as a profound redesign of energy and material flows in sectors as diverse as: housing, agriculture, transport and industrial systems.

Many of the characteristics of a partnership can be both weaknesses and strengths. A focus on the quality of the processes that constitute the building of relationships in a partnership and an awareness of the context of those processes can help to ensure that these dualities are used as drivers of innovation, rather than act as detriments to the partnership. In a River Catchment Partnership such as the Mersey Basin Campaign, these processes can be broken down into three main areas: Partnership Development; Strategic Planning and Coordination and Collaborative Planning and Organisational Learning. Important characteristics of these processes that emerged from this research are summarised below.

Characteristics of Process Quality

Partnership Development

· actively seek partners and broaden network

· ensure equitable representation of interests

- encourage involvement in decision making

- non judgemental, providing a neutral environment

- pay conscious attention to quality and clarity of communication

- create time and space for partnership development

- create opportunities for informal interaction

- value

work of partners

Strategic Planning and Coordination

· expanded view

- large geographic unit

- long timescale

- broad nature of aims

· start small with projects that lead to success stories

- maintain links between local actions and strategic aims

- synthesise bottom-up and top-down planning process

· different focuses for engaging partners in action – cross boundaries

- allow for changeable nature of networks – fluid connections in time and space

Collaborative Planning and Organisational Learning

· create opportunities for organisational learning

- horizontal skills sharing, to increase adaptability to changes in personnel and partners over time

· create opportunities for a high level of engagement in planning process

- develop

effective process of collaborative planning

- co-ordinate

gathering and integration of data

- facilitate

broad access to data to facilitate collaborative planning

- incorporate

integrated sustainability principles into planning process

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that the processes of maintaining a partnership are key to increasing its effectiveness in planning and integration. A complex partnership has tensions and dualities, which can create problems at many times during its evolution. Collaborative planning processes can help utilise these tensions to enhance innovation and dialogue, but require continuous attention and learning of new skills by Campaign staff and partners. The fact that there is no easy way to simultaneously improve the natural and human environment should not come as a surprise.

The surprise lies in the depth of learning about processes that could help to bring about such changes, which the experience of the Mersey Basin Campaign can offer. The next ten years should prove to be a further valuable learning experience.

Acknowledgements

and Further Research

The research was conducted as partial fulfilment of the requirements of an MA Econ. in Social Research. It is part of a larger research project conducted by the author entitled "A Participatory Protocol for Ecologically Informed Design Within River Catchments". This research will focus on the process of collaborative planning in the Mersey Basin Campaign, in the context of the European Union Water Framework Directive (EC 2001b) . It is supported by the Mersey Basin Campaign and the Economic and Social Research Council. The Ph.D. supervisors for this project are:

Professor John Handley, Groundwork Professor of Land Restoration and Management , School of Planning and Landscape, University of Manchester

Joe Ravetz – co-ordinator of the Centre for Urban and Regional Ecology, School of Planning and Landscape, University of Manchester

Jeff Hinchliffe – Chief Executive, Mersey Basin Campaign

Further information about this project

www.holocene.net/sustainability/MBC-research.htm

Recommendations For the Campaign

Whilst the Campaign has achieved remarkable successes in over 15 years of operation, and has developed many successful mechanisms for enhancing partnership working, this research has uncovered possible improvements to take it forward in the next 10 years. These recommendations fall under three headings:

A.

Opportunities for organisational learning

B.

Increasing the quantity and quality of collaborative planning

[4]

processes

C.

Support for RVI programmes and investing in skills training

Recommendations to expand existing programmes are particularly relevant in the light of the increased importance placed on participatory processes within the emerging sustainable development agenda and, specifically, the requirements for participation introduced by the newly enacted European Union Water Framework Directive (EUWFD) (EC 2001a) . Discussions of implementing the EUWFD point to the long-term cost benefits of enhanced stakeholder participation in planning. A potential major obstacle to successful implementation is underestimating the human and financial resources required to facilitate this participation (Jones 2001, pg. 19) .

Interviews with partners suggested that the input of community and voluntary sectors into the Campaign has been a hallmark of its excellence, as recognised by being awarded the International RiverPrize. A significant factor in building partnerships that emerged from the analysis was that it takes time to develop relationships and build effective networks. Changes recommended below should be made in consultation with the partnership, to ensure that they build on its unique strengths.

The recommendations for RVIs receive extra impetus from the Campaign's shift towards a greater operational focus, with an emphasis on the RVIs as a major delivery mechanism (MBC 2001a) . These changes will require an expansion of existing support and training programmes. In a time when the need for skilled people to facilitate community projects and promote integrated thinking is emphasised, the Campaign can play a key role in helping to define a new "sustainability professionalism" (e.g. WWF-UK 2000; Knowland and Ali-Khan 2001) .

A. Organisational learning

· Allocate designated sessions for pooling of best practise at managers meetings, RVI chair and coordinator meetings. These could include discussions with the wider Campaign staff, to bring in different areas of expertise and experience.

- Expand mechanisms for giving recognition to originators of best practice – enhancing professional development and motivation for making the information widely available.

· Enhance educational value of award schemes through case study materials and site visits (e.g. Dragonfly Awards and Business and Environment Awards).

B. Collaborative planning processes

C. RVI programme support and skills

training

· Improve operational efficiency of RVI coordinators by providing increased fundraising and administrative support from the Campaign Centre.

· Expand existing skills training programmes. Offer increased training in: participatory facilitation skills, strategic planning, use of GIS in project planning, integrating programmes into formal Education at multiple levels and communication skills. Much of this additional training could be project based, to help RVIs achieve objectives at the same time as enhancing skills.

- Further develop capacity in the Centre to provide supplementary support for RVI projects that would otherwise

be outside the scope of one RVI coordinator. This could include resources to provide

assistance and extra skilled personnel for participatory planning and programme

design. As the need for this support varies over time in the different RVIs,

this could be an effective use of support from the Centre.

References:

EC (2001a). Strategic

document, Common Strategy on the Implementation of the Water Framework Directive.

Paris, Sweden, EU Water Directors, European Commission, EU Member States:

71.

EC (2001b). Water Quality

in the European Union - The EU Water Framework Directive, Europa Website,

European Commission. 2001.

Jones, T. (2001). Implementing

the EU Water Framework Directive: A seminar series on water Organised by WWF

with the support of the European Commission and TAIEX, Synthesis Note Seminar

3: Good Practice in River Basin Planning. Brussels, WWF, European Commission,

TAIEX: 31.

Knowland, T. and S. Ali-Khan

(2001). Sustainable Development Professionals: who needs them? EG April:

10 - 13.

MBC (2000). Mersey Basin Campaign, Progress Report

1985 - 2000, Building a Healthier Economy Through a Cleaner Environment.

Manchester, Mersey Basin Campaign.

MBC (2001a). Mersey Basin

Campaign, Corporate Plan 2001 - 2004. Manchester, Mersey Basin Campaign.

MBC (2001b). The Next Decade

- A Summary. Manchester, Mersey Basin Campaign.

NWRA (1993). Regional Economic

Strategy for North West England. Warrington, North West Regional Assembly

and North West Business Leadership Team.

Watson, N. (2001). Creating

Effective Partnerships for River Basin Development: An Evaluation of the Fraser

Basin Council, British Columbia, Canada. Lancaster, Department of Geography,

Lancaster University, Faculty Research Program of the Canadian High Commission,

London and the Institute of Environmental and Natural Sciences: 31.

Wood, R., J. Handley and S.

Kidd (1997). Mersey Basin Campaign - Mid Term Report - Building a healthier

economy through a cleaner environment, Mersey Basin Campaign.

Wood, R., J. Handley and S.

Kidd (1999). Sustainable Development and Institutional Design: The Example

of the Mersey Basin Campaign. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management

42 (3): 341-345.

WWF-UK (2000). Professional

Practice for Sustainable Development, Book1: Building support within the profession.

Bourne, Professional Practice for Sustainable Development - Project Management

Group, WWF-UK, Council for Environmental Education, The Environment Agency,

The Institution of Environmental Sciences, The Natural Step, UK: 8.